You’re walking down the street and you see this girl. And you look at her, and she looks at you… So you smile at her and she smiles at you. You saunter over towards her – and she hands you a white feather, saying, “You should be in uniform.”

In late 1914 and in 1915 that scene was happening every day, all over the country. Were the women who handed out emblems of cowardice to strangers just obsessed patriots? Were they “flappers” who had caught “khaki fever”? Or was there more to it than this? I want to try to understand the phenomenon by looking at the stories that people told each other.

The term “white feather” came from cock-fighting. Some game birds had white feathers in their tail, and so to show the white feather was to turn tail. “Showing the white feather” was a term used for human cowardice throughout the nineteenth century. The OED dates the usage from 1795.

There doesn’t seem to be any reference to anyone presenting feathers as a sign of disapproval until 1902, when A.E.W.Mason published The Four Feathers. This has been an enduringly popular story, and over the century has been filmed at least six times, but to understand it we need to remember that it was written at the time of the Boer War, when there were considerable anxieties about the fitness of recruits for the British army, and the quality of British manliness.

The story goes like this. Harry Faversham decides, for practical reasons, not to go with his regiment when they leave to fight in the Sudan. His fellow-officers see this as cowardice, and three of them send him a white feather each, together with their cards. His fiancé Ethne discovers this, and she too plucks a white feather from her boa, and breaks off the engagement.

Harry is forced to scrutinise his motives, and recognises that cowardice played a part in his decision. Silently, he decides to regain his reputation, in his own eyes and those of others by going secretly to the Sudan. He redeems himself by acts of gratuitous courage, by enduring suffering, and by rescuing some of his old officer comrades from a vile Sudanese prison. Having proved his manhood and returned the feathers to their donors, he returns home to reclaim his fiancé and the approbation of his estranged father.

It is a book full of silences. Harry Faversham cannot tell his father, the General, how he feels about a military career; the family friend is prevented by convention from beginning a conversation that might have relieved Harry from his sense of isolation. The book is full of undelivered messages and people unable to declare their feelings. Yet within this culture of reticence, heroism triumphs.

In the context of the Boer War, The Four Feathers can be read as a consoling fable – Harry Faversham realises that he is found wanting, but he does something about it. So can England.

The degree to which this story had resonance for the age can be judged from the way in which it echoes through popular culture. In 1908, for example, the two most prestigious boys’ papers, The Boy’s Own Paper and The Captain both ran serials called The White Feather. The more interesting of these is the serial in The Captain, an early piece of fiction by P.G.Wodehouse, which transfers the pattern of The Four Feathers to a public school. Sheen, a scholarly sixth-former avoids involvement in a fight between some of his fellow students and some ghastly common oiks from the town. He is sent to Coventry by the school, and, facing that silence, redeems himself by recognising his fear, secretly learning to box, and achieving honour for the school in the Public Schools boxing championship at Aldershot, before the approving eyes of the military. Like Harry Faversham, he proves himself by his own efforts, pursued in secrecy and silence.

We can take it that everyone knew the meaning of a white feather in September 1914 when a retired Admiral called Charles Penrose Fitzgerald organised thirty women in Folkestone to hand out white feathers to any men that they saw not in uniform. This was reported in the press, and the custom spread, so fast that it actually worried the authorities – they wanted recruits, but they didn’t want a popular movement that might get out of hand. It certainly worried a lot of men, as we can see by the stories they began to tell.

These stories can be represented by a passage I found suddenly appearing in the preface to a book called The Minor Horrors of War, which is actually about insect life – the lice and fleas and so on that afflict soldiers in trenches. It is a comment on:

“…the half-hysterical ladies who offer white feathers to youths whose hearts are breaking because medical officer after medical officer has refused them the desire of their young hearts to serve their country…”i.

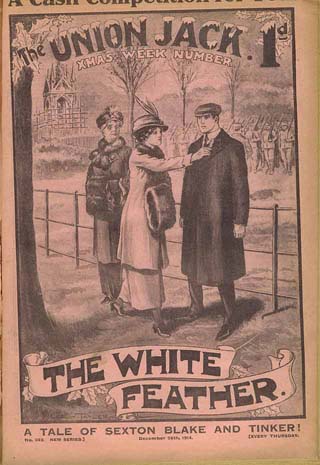

A different version of the story appears in the Union Jack comic for December 26th, 1914, in which “a girlish figure wearing a badge of some sort on her breast” sees a young man wearing tweed and a heavy overcoat. Her mother, sensing the young man’s “troubled look”, tries to stop her, but the girl says, “I don’t care, mother… I think it’s a shame that any healthy young man should be lounging here while his countrymen are training themselves, ready to meet the enemy.”… and the scrap of white was thrust into his buttonhole. What the insensitive girl doesn’t know is that the young man is really desperate to fight, but is being prevented from enlisting by his selfish father.

The hit play on the London stage in 1915 was a comedy thriller, The Man who Stayed at Home by Lechmere Worrall and J. E. Harold Terry – so popular that it was later turned into a novel. This features a silly-ass character called Christopher Brent. Everyone is saying he ought to join the army, but he pretends not even to understand them. We, the audience, know that he is really a spy. The scene that made the biggest impact is one where an earnest young woman gives him a white feather; he uses it to clean his pipe, and then cheerfully hands it back to her. We know that he’s really the bravest of them all. The silly girl has been misled by appearances.

Urban legends abounded, too – the stories of what happened to a friend of a friend, so they’re definitely true. There’s the woman who gives a feather to a man in civilian clothes on a bus, and when he stands up everyone sees that he has only one leg. There’s the story of the girl who gives a man a feather, not realizing that he’s just been awarded the V.C. The typical structure of these stories is very different from that of the Four Feathers, as you can see from this table:

|

Four Feathers |

Wartime stories |

| Woman sees the sign of cowardice | Woman sees the sign of cowardice |

| Man recognises his cowardice | Man knows he is not a coward |

| Man retreats to silence, then proves his courage | Man speaks, or shows wound as sign of courage |

| Woman recognises his courage | Woman recognises his courage |

| Man and woman marry | Woman retreats |

| Man has more status than before | Man has more status than before |

Surely the widespread need to tell such stories suggests a considerable anxiety, as well as hostility to the women who gave out the feathers. So why were men so very disturbed by this practice? Why did women continue giving white feathers in the face of such hostility? Which women did it?

It’s hard to find out which women were involved in the practice. In the 1960s the BBC were making a documentary, and appealed for people who remembered white feathers being distributed. According to Nicoletta Gullace, hundreds of men responded with anecdotes like the ones I’ve mentioned, or with stories of men who died after being recruited this way. Only two women admitted to having presented feathers, one of whom described herself as a “chump” for doing so.

The women have disappeared. Contemporary accounts often call them “flappers”, but that was a term generally used to belittle women that someone disapproved of. It is likely that many of the givers of white feathers were young girls of the type described by Angela Woollacott in her article on “Khaki Fever”. The outbreak of war led to a huge interest in soldiers among teenage girls, who sometimes became “aggressive and overt”x in their attention to the military. Sometimes they even hunted in packs; Woollacott describes “Colonials running for their lives to escape a little company of girls.”

Is that the whole story? I don’t think so. The important factor is that for many women the war was understood as a gender issue.

Britain’s main stated reason for entering the war was the German invasion of Belgium, which broke the treaty guaranteeing Belgian neutrality – the famous “scrap of paper”. On August 8th, The Nation magazine could say, “It is a passionless war. No one hates anybody, not we the Germans, nor the Germans us.” There was no such anger, the magazine said, “as was evoked against the Boer Republic in the summer of 1899.”

But then the atrocity stories began. The massive German army, heading into hostile territory, was troubled by memories of 1870, when French civilians had acted as franc-tireurs (free-shooters), and had engaged in guerrilla sniping against the invaders. They took punitive action against any hint of civilian activity, shooting hostages, burning buildings, and so on. Some soldiers indulged in their own individual petty vengeances against the hostile population, too. There were thefts, there were petty acts of vandalism, like defecating on people’s carpets, and there were some rapes.

It was these that inflamed the imagination of the British public. The war changed from being about the violation of a treaty to being about the violation of women. (It is hard to be completely certain, but this seems to have been a grassroots, bottom-up redefinition., coming from popular feeling about newspaper reports and rumours, before it was a theme picked up by the official propagandists and poster artists.)

Discussion of this was made more potent by circumlocution, by reminders that it was something that could not be discussed. What the Germans had committed were unspeakable acts, or “deeds so terrible that they could only be whispered from man to man”, as the Labour Politician J.A. Seddon called them. And of course, as they were whispered, Chinese-style, they grew in scale and horror.

Here is another image, from a march in favour of the war effort organised by the Women’s Political and Social Union, a woman dressed to symbolise suffering Belgium. As Michael McDonagh described her: “She carried aloft the flag of her country, torn and tattered but still beautiful… She walked barefoot through the slush of the roadways… and on her face there was an expression of pride and sorrow and devotion, all of a high degree…”

The Women’s Political and Social Union was run by Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst, and was the most prominent militant Suffragette organisation, which might remind us that disturbing images of male violence to women were not unprecedented in this period. The issue of The Suffragette printed the week before war was declared looked like this –

Suffragettes were no strangers to militaristic thinking; for several years they had been treating Britain as a war zone. Inside this issue there is a double page of reports of window-smashing, arson and other activities. It is headed “News from the Front”.

Famously, Mrs Pankhurst at the start of the war called off her campaign of militant law-breaking, and threw herself and her movement into energetic support for the war effort. Angela K. Smith has shown how this U-turn can be explained in three ways:

-

A genuine patriotic belief in the war

-

A sense that the tactic of extreme militancy was becoming counter-productive, and would become more so in wartime

-

A sense that war was a chance to re-define women’s role, and to re-define the meaning of citizenshipvii

From September 1914, Mrs Pankhurst advocated “War Service for All” – conscription for men and compulsory war work for women. At this time, the Government did not want conscription (They had more volunteers than they could train) and male writers wrote about “The insult of conscription” because it implied that British men would not fight unless forced to.

Mrs Pankhurst was adamant, though:

“The least that men can do is that every man of fighting age should prepare himself to redeem his word to women, and to make ready to do his best, to save the mothers, the wives and daughters of Great Britain from outrage too horrible even to think of.”

She drew attention to the fact that some women were doing a great deal for the war effort, while some men were not, calling into question the basis on which the right to full citizenship was judged.

We need not totally believe Sylvia Pankhurst, who as a pacifist had disagreed with her mother on this issue, when she caricatures the war efforts of her mother and Christabel:

“Mrs Pankhurst toured the country making recruiting speeches. Her supporters handed the white feather to every young man they encountered wearing civilian dress, and bobbed up at Hyde Park meetings with placards, “Intern Them All.”

As Nicoletta Gullace has said, “The spectre of Belgian atrocities greatly enhanced women’s authority to speak to men in this way.” It gave permission to ignore the rules of conventional behaviour at a time when conventions were strict – not merely talking to strange men in the street, but assuming that a woman had the right to inform a man of his duty

It would be wrong to think that the suffragettes were “behind” the white feather movement, or that their participation was more than a small part of a far wider phenomenon.

These soldier-worshippers may seem very different from suffragettes suspicious of male power, but as Woolacott says, “This assertive behaviour by young working-class women threatened a subversion of the gender as well as of the moral order.Handing out white feathers was even more subversive.

What is significant about the involvement of the suffragettes is that it makes explicit what was otherwise unspoken – women were claiming the right to inform males of their duty, and were demanding that they fulfil the obligation implied in the restriction of full citizenship and the franchise to males, the obligation to defend their womenfolk..

Many men must have been made to feel very uncomfortable. During the years of peace it had been possible to think of oneself as manly without being in any way military, but now gender stereotypes were shifting, and in a way that left men little room to manoeuvre. Even young girls were encouraged to think of themselves in a militaristic way; all sorts of women were urging men to enlist, not just the predictable conservative patriots like Mrs Humphrey Ward. Now even the suffragettes, who before the war had seemed to offer a different kind of thinking about gender, were joining in.

Men must have felt themselves the subject of a formidable female gaze, which left some little choice but to enlist. They did so in silence. Time and again in narratives by men, the moment of enlistment is not spoken of.

“What the psychological processes were that led to my enlisting in “Kitchener’s Army” need not be inquired into. Few men could explain why they enlisted”, says Patrick MacGill at the beginning of The Amateur Army.

This is dramatized very well in a Dornford Yates short story. The hero has just heard about the outbreak of war:

“Leisurely he began to fill his pipe, and a moment later he fell a-whistling the refrain whose words they had been singing together. Abstractedly, though, for his brain was working furiously. Dolly Loan never took her eyes from his face. He did not look at her at all.”

In that silence, under the female gaze, he makes his decision and joins up. Otherwise he’d have had to award himself the white feather.

References:

- Nicoletta Gullace, The Blood of Our Sons (Basingstoke, 2002)

- Angela K Smith : Suffrage Discourse in Britain during the First World War, 2005

- Angela Woollacott, “ ‘Khaki Fever’ and its Control: Gender, Class, Age and Moralityon the British Homefront in the First World War”, Journal of Contemporary History Vol 29 (1994) 325-47

- Shipley, The Minor Horrors of War, London 1915

- Union Jack, December 26th, 1914.

- The Suffragette April 23rd, 1915

- Sylvia Pankhurst, The Suffrage Movement, 1935

- Patrick Macgill The Amateur Army (1915)

- Dornford Yates, “And the Other Left” collected in The Courts of Idleness (1920)

41 Comments

In the Native American the name Whitefeather stands for purity and is translated to Bravest of the brave. Interesting that 2 different cultures have different meanings for a White Feather

Understandable that the two cultures see it differently.

white feathers in a european concept are a sign of turning away from a fight. “all his wounds were in front” was often the only comfort the dead soldier’s family could receive…

feathers in a native american concept are a mark of achievement–since IIRC, the first feather had to be obtained during some test of manhood… badge of rank, etc…

different attitudes about fighting style were also present (see stories of the “French and Indian War” as it was called)… native americans were more likely to melt away using fieldcraft than stand out in the open blazing away at the enemy wearing brightly-colored uniforms…

maybe it also depends to a large extent on whether one sees birds as noble spirits or not?

Hello! Mr. Simmers, Until I read a book called” Maise Dobbs”, that takes place in England during WWII, I had never heard of The White Feather Society. Thank you for your very interesting and informative article! Perhaps you might give me a few suggestions. I’m writing a paper after taking two law classes; Civil Rights and

Moral Reasoning and The Law, at the Univ. ofPittsburgh. I am using the theme of tiranny of the masses during both World Wars against consciencious objectors in the USA and The White Feather Society of England.I find it amazing that a majority

opinion was used in such unfair and ugly

ways against a country,s own citizens. Any sources or opinions you may want to pass on will greatly appreciated!

With regards, Jude

Judith – Thanks for the comment. The best book about the White Feather movement that I know is Nicoletta Gullace’s “The Blood of Our Sons”, which has a lot of interesting (and sometimes unexpected) things to say about relations between the genders during wartime.

You’re the second person to recommend Maisie Dobbs to me. I must find out more about her.

The feminist lesbian men haters simply used it as an excuse to get rid of young men. If Pankhurst and her lezzer mates had had their way, they would have been happy to see every male slaughtered in battle.

If one of those dykes had offered me a feather I’d have shoved it up her where the sun doesn’t shine.

I am a soldier from England Mrs Pankhurst was not gay and loved men just not obscene classless men like you Sir. And she had more courage than you probably, if you really want to learn about her and the women and MEN who fought in that struggle. A new movie called suffragettes will help. And then tell me these women who were beat on a regular basis as we’re many in their day are not heroes.

Dear Martin,

Thank you for your comment, the language of which helps to explain why many women choose to become militant feminists.

Which came first, the militant feminists, or the hostility to them?

The term militant feminist being an irony,since they only practice militaristic tactics against their own people rather than the enemies at the front line!

Besides,if a mere act of defending oneself can provoke the aggressor into outright violence,does that not prove the aggressor had the very intent on such violence in the first place?why should anyone suffer insult and harassment and not fight back against it?

Your post captures the issue peyerctlf!

The book is a ‘Maisie Dobbs Mystery’ called Birds of a feather, by Jacqeline Winspear, set in 1930. It is a nice read.

There are several murders of young women, the murderer finally being found as as woman who had lost a husband and three sons, with a fourth son irredeemably damaged, all of whom had joined up after being presented with a white feather by the young women murdered.

It is pleasantly written, and I enjoyed it.

But it had an effect on me as I have known about the white feathers, but never before considered how those who indulged in handing them out felt after they saw the carnage of the young men in the war.

How could they know what they were doing. I think many (if not all) must have had truly remorseful feelings afterwards.

Interesting slant on the suffragettes. (The suffragists under Millicent Fawcett, who had been campaigning since 1866, always advocated legal means of obtaining female/universal enfranchisement.)

I must read Nichola Goolace’s book as well. Nice article, thanks.

Sylvia Pankhurst was, and remained, a pacifist and a socialist all her life, and split with her mother and sister at the time of WW1 over these issues.

Tip top stffu. I’ll expect more now.

Morning George! I think it is fairly noticeable in the fiction of the period that the stories of giving a white feather were regarded with distaste or even disapproval by the men who might have been on the receiving end (ie men of the right age), but were approved of by men who were too old to fight, ie the fire-eaters. Also noticeable are the women’s views: in general the young and silly women, or women old enough to know better but who are also silly, approve of the giving of the WF, whereas ‘sensible’ women don’t. There is a definite sense of division, with the giving of the WF being an emotive even, something spurred on by an emotional urge rather than by mature consideration.

A terrific essay — I was researching the meanings of my own name when I came across it! Jennifer is variously said to mean white feather or white wave.

In stepping back, it’s kind of inspiring that, to look at the whole picture, the giving of a white feather could be seen to be less about men’s cowardice and more about women’s courage – stepping out of a rigid, pre-defined role.

And also, in that case, to be much more in line with the Native symbolism.

It’s always been curious to me that while we understand male courage, integrity, and generosity of spirit, we tend to overlook ascribing any of these positive qualities to women!

Really Jennifer? With all due respect, as a man, I find this an inappropriate cause to celebrate a woman’s courage in such a way. I’m not talking about you personally but I would be ashamed if I were one of those girls exercising boldness in this regard. It is similar to a woman celebrating her ability to make important family decisions, in say the raising of children, by deciding to have her son circumcised. I mean could women please exercise their new freedoms and rights in some way that does not result in violence happening against men? After all, women are stereotyped for their compassion and grace and sensitivity and nonviolence, right? Right? Therefore I am perplexed. No disrespect to you personally. Not to put you down. It may have taken courage indeed for women to break out of their roles, but what takes more courage- handing out a white feather telling a man what he should do with his life, or actually enlisting to go to a far away land and then going there and fighting in the trenches? I can see how someone with combat related loss of body part or trauma, in any war, might resent what you are saying here. Still it did take a wee bit of courage to break this role.

Jennifer, I hope every woman finds true courage, but first finds compassion

I guess what they found was the courage to manipulate 🙂 That doesn’t count as courage to me.

Please don’t delude yourself by thinking there was anything courageous about what these women did. There wasn’t.

I read somewhere about a mature looking boy of 15 during WW1 who was given a white feather by a girl on a bus. His mother recalled bitterly how, through shame, he lied about his age, enlisted and died before his 16th birthday.

I would like to use this in an essay but have forgotten where I read it for reference. Anyone recall it at all.

More on the white feather: the poem ‘Jingo-Woman’ by Helen Hamilton fiercely criticises the practice of giving a white feather in WW1, and makes the point that such women had better be prepared to fight if they too are called up when all the men are dead. I hadn’t come across before the suggestion that women being called up might have been a possibility in WW1, even in principle. The poem has been reprinted in Scars Upon My Heart (ed Caroline Reilly), but is out of print (through freely available second-hand).

Hi,

We are interested in using the White Feathers picture in our book.

Do you know where I could find the Union Jack, December 26th, 1914.

Many thanks,

Joan

Thank You for a thoughtful and informative essay. I’ve been studying the connections between war and gender and their relations to motivation, and appreciate your ideas. I recommend you check out an interesting article in JSTOR on the topic: Gullace, Nicoletta F. “White Feathers and Wounded Men: Female Patriotism and the Memory of the Great War.” The Journal of British Studies 36, no. 2 (April 1997): 178-206.

Bill

Mrs Pankhurst took a U turn from her organized terrorism, because she realized it was an effective if not amusing way to dispose of the adult male population.

Getting rid of men in huge numbers, allowed woman to inherit the dead mens property and wealth. Redistributing it all to her gender.

Destroying Britain’s male culture through wholesale slaughter, would mean the new generation’s of boys would be bred, in a world where female narcissism and immunity is the only thing of concern.

One can only wonder at her sense of female empowerment, with all the dead, the ravaged bodies and broken minds.

She truly was a roll model for the modern feminist woman today!

Roderick!

I am a gay male that works for a national civil rights law firm, and I find the history of feminism disturbing to say the least .

A principal aim of the suffragettes was to disturb males (whether gay, straight or reserving their decision). Essentially they called the male bluff: ‘You say that you alone deserve the vote because you alone might have to fight for your country. So get out there and fight…’

and so… they did. And died in great numbers.

Feminist today and even in the past have a history of hating men even gay men . I have no idea why feminsim still exist. Women have the full state and federal rights as men do yet scream and yell louder than any gay male that is fighting for the 1700 state & federal rights they are lacking plus gay men are the most beaten , killed and discriminated minority in America

Never much thought here about the 3 million British men who had bits of their heads blown off, arms and legs mangled for the rest of their lives, and mental faculties gone forever, no what is the most important is that a few upper class women fought for their rights,,typical self obsession by females.

Over 90% of the British soldiers did not have a vote until 1918, they did not elect the people who sent them into harm’s way. Men paid a terrible terrible price in cold trenches, virtually no British women died in WW1. Females were given the vote a few years after men, FOR NOTHING! Men were and remain disposable

What an interesting article and series of responses. Really good to read – thank you. You may be interested in a growing international symbol of recognition for family and friends of service people, TheSRF. It provides people in the services with an opportunity to thank family and friends who provide them with significant support by awarding them a silver feather. I see it as a lovely coming of age of the relationship between people, embracing the feather for it’s more uplifting and graceful inferences once again.

I am kinda disturbed by the desires by some to try and justify the disgraceful white feather campaign.

Try as you might, George, it was still a collective campaign we can all see the folly of. Most if not all of the women who took part in the white feather campaign were utterly ashamed of themselves and rightly so, yet only two of them were brave enough to publicly admit it.

To carry it out over such selfish reasons of revenge and personal gain on the back of human suffering – no matter what the cause – is absolutely repulsive. Serving men were on the receiving end, as were the underage, unfit, and discharged.

And what’s more, women still have the nerve to blame men and masculinity for all war while they fail to remember their own contributions to slaughter and armed conflict.

Lest we forget.

I do like your table for the four feathers and wartime stories. There is one good and obvious reason why the man has more status than before at the end – the books that certainly wouldn’t have been written at the time:

Woman sees the sign of cowardice…

Man is publicly shamed…

Man then attempts to prove his courage…

Man finishes up being reduced to a fine red mist / drowning in freezing cold water / gets gassed and drowns in the blood and blisters that his lungs are filling with / contracts dysentry / comes back with distinctly fewer limbs than he left with or a concussive brain injury / came back with what amounts to a modern diagnosis of PTSD, and that it was quite likely that all but the most severe cases wouldn’t actually be counted as “wounded” or “sick”…

Woman might work in a munitions factory (“lower” classes) or a nurse (“middle-upper” classes) or just fund-raise for the war effort …

Inside ten years of the end of the war there is universal sufferage for both women and the 90% of men who didn’t own property (but were still expected, and then compelled, to enlist). So man (assuming that he survived) on average has more status than before…

Two in seven UK combatants were wounded in action, one in seven was shipped back in a box or not at all. Is it any great surprise that after the fighting was over, everyone realised what a charnal house it had been, and the women in question had grown up a bit, that few would admit to it more than fourty years later?

Ask yourself if this is more or less likely than the hundreds of “anecdotes” and “urban myths” having been made up? Especially as the government at the time issued more than a million silver war badges for those who had been discharged through illness or injury and goodness knows how many “King and Country” badges for those men who were engaged in civilian war work.

Blue –

In fact, it was not totally impossible for a story such as you suggest to be published during wartime. Something of the sort can be found in The Last Weapon: A Vision by Theodora Wilson Wilson, published by the pacifist firm of C.W.Daniel, 1916. A soldier comes back from war to accuse those who encouraged him to go, telling stories of battlefield horrors, executions for cowardice and so on.

One might also think of Sassoon’s poem ‘They’, in which the Bishop who has preached the glory of war is confronted by the reality of what it means for soldiers.

During wartime, though, such texts only found a minority audience.

Hi,

Just wondering how you cleared copyright for the cover of the ‘Union Jack White Feather’. We’re interested in using it on a documentary?

Thank you.

I got it – with permission, as I recall – from a Sexton Blake website that is now defunct.

A most interesting, thought provoking, read on human behaviour and motivation, particularly concerning the apparently very powerful insiduous group effects on individual morals, motivations, and behaviour inspite of their personal convictions and willpower.

Where did human’s much prized individual free willpower go to?

I wrote my dissertation at portsmouth university on this subject. I read nicoleta gullace’s book and in my time at the imperial war museum and the bbc archives at Caversham could not find many of the sources used to base arguments on, furthermore on presenting my findings to the university of portsmouth I had my work down graded for challenging perceptions about how the state in britain used gender based propaganda. My argument was based on research that women were used as a labour force and as a basis for emotionally charged chivalric propaganda purposes then they were used as scapegoats by those returning from the front. As I said I brought the book to the imperial war museum the archivist told me those sources didn’t exist, don’t believe me go there find out. I was told at portsmouth university to conduct research from primary sources to attain the best marks, but because my work challenged the accepted accounts it was dismissed even though I was basing my work on contemporary accounts and the latest historical research. I spoke to my tutor a female lecturer at the university who told me she thought my work was constructed well and thought that my research provided a source based challenge to the accepted historiography. However my work was passed to a gender based professor at the university who market my work rated a first down yo a 2.2, wether by accident or not notes were left in my dissertation when I picked it up at mildam building saying she did not like my use of gender based argument, and that for me (a man) it was not appropriate. Further to this it turns out that this professor had been working on a body of work that my sources and argument disagreed with. When I challenged my lecturer on the made up sources I was told that sometimes historians in need of source material to fit their argument do bend the truth and basically I should wise up. Needless to say I have lost faith in the ivory towered closed minded historical community who seem intent and have too much interest in challenging the accepted historiography.

It sounds to me as though you’ve got grounds for appeal against her mark.

Can you give examples of the sources that don’t exist?

Hi George. I’ve found an 18thC ref to presenting the white feather to a man to indicate disapproval for his lack of courage, in The Memoirs of Madame de La Tour du Pin. This text was written in stages in the 19thC, until the 1850s, and not published (in French) until 1906. She recounts an episode during the Revolution when a general was sent a white feather in an envelope anonymously as a response to his refusal to take a decisive (military) step. It’s at the beginning of Chapter 12. It’s possible that this is also the same event that the OED example refers to, though I think it’s a little earlier, since it happened before the Terror.

Thanks. that’s an interesting one. I wonder if the trope originally came from the French.

In Alan Sillitoe’s splendid history of his family in the context of the Great War -‘Raw Material’ you find the following on pp.119-120 (Star edition, 1978):

“All sorts of tricks and pressures were employed to get men into the army in the two years before conscription came. Those of a certain class who did not hurry to join up finally capitulated when nanny met them in the street and handed them a white feather for cowardice. My Uncle Frederick, who said that this became quite common, was offered one on the top deck of a tram by an elderly woman. Instead of blushing with shame he gave her a violent push: ‘Leave me alone, you filthy minded old butcher!’

Then he made his way off the tram expecting to be pursued by howls of ‘universal execration’ from other passengers, but they were embarrassed and silent, so that he walked down the steps unmolested.

This nanny appeared to have mistaken him for some type he clearly was not. They seemed determined, he told me, to get their revenge on those young gentleman whom they had been forced to spoil and mollycoddle as infants. They also possessed more than a residue of spite against the parents they had been bullied by, and retaliated now by hurrying their pet sons into the trenches – or any sons they could get their hands on, for that matter. It was one more example, he added, of how war puts the final touch of degredation on certain people to whom it has already got a fair grip. Not that this was meant to malign women. Far from it. Men did the fighting, after all.

In war it is the worst of a country that persuades the best men to die…He thought it was a case of the old wanting their revenge against the young”.

(‘Raw Material’ was originally published by WH Allen & Co.)

The white feathers motif is one of the most common shorthand of the great war.

I use it in my play and novella ‘The Prisoner’s Friend’ almost because it is expected in a play of that kind

Peter Drake

Playwright and teacher

Hexham Northumberland

9 Trackbacks/Pingbacks

[…] White Feathers : Stories of Courage, Recruitment and Gender at the start of the Great War « Great W… Surely the widespread need to tell such stories suggests a considerable anxiety, as well as hostility to the women who gave out the feathers. So why were men so very disturbed by this practice? Why did women continue giving white feathers in the face of such hostility? Which women did it? (tags: gender ww1 suffragettes conflict) […]

[…] https://greatwarfiction.wordpress.com/white-feathers-stories-of-courage-coward… […]

[…] [White Feathers : Stories of Courage, Recruitment and Gender at the start of the Great War] […]

[…] https://greatwarfiction.wordpress.com/white-feathers-stories-of-courage-cowardice-and-recruitment-at-… […]

[…] [image] illustration for Arnold Bennett, “The White Feather: A Sketch of English Recruiting,” Collier’s Weekly (U.S.), Oct. 10, 1914. Thanks to George Simmer at Great War Fiction. Here’s an essay by George Simmer on white feather stories. […]

[…] About: Feather is about the White Feather Campaign, a monstrous 20th century peer-pressure campaign responsible for the deaths of many thousands of young men. Find out more here. […]

[…] Frauen reichlich Gebrauch. So reichlich, dass zahllose tragische Schicksale die Folge waren. Eine Kleinanzeige in der Times vom 8.7.1915 verdeutlich es: Jack FG. Wenn du nicht bis zum 20. in Uniform bist, dann […]

[…] Frauen reichlich Gebrauch. So reichlich, dass zahllose tragische Schicksale die Folge waren. Eine Kleinanzeige in der Times vom 8.7.1915 verdeutlich es: Jack FG. Wenn du nicht bis zum 20. in Uniform bist, dann […]

[…] Frauen reichlich Gebrauch. So reichlich, dass zahllose tragische Schicksale die Folge waren. Eine Kleinanzeige in der Times vom 8.7.1915 verdeutlich es: Jack FG. Wenn du nicht bis zum 20. in Uniform bist, dann […]