Regular readers of this blog will know that I am rarely so enthusiastic as when exploring old issues of the Magnet comic, in which ‘Frank Richards’ each week delivered new instalments of the exploits of Harry Wharton, Billy Bunter and co. at Greyfriars School.

Visiting Hull just in time to catch the deeply enjoyable Philip Larkin exhibition at the Brynmor Jones Library, I was delighted to learn that Larkin was possibly even keener on Greyfriars than I am.

The great joy of the exhibition is the opportunity to nose around Larkin’s bookshelves. The bulk of his book collection is now stored at the Library, and this exhibition puts it on display. There is a large poetry section, as one might expect, and all the Eng Lit standards. Only one of the books was opened to show Larkin’s abusive marginal comments. I’d like to have seen more.

The display gives a rough idea of which authors mattered to Larkin. There is a large Hardy section, as one might expect. There are a lot of books by or about D.H.Lawrence, which suggests that Lawrence mattered to him more than one might have suspected from the poetry. I was glad to see a reasonable showing of Rose Macaulay and Arnold Bennett and the complete run of A Dance to the Music of Time, but it’s the popular fiction choices that really show Larkin’s enthusiasms.

There is a long shelf of Agatha Christies. The complete works? Not far off it, I’d guess. Almost as many John Dickson Carrs, too (I recently read one of his for the first time since my teenage years, and found it a bit of a plod – though the denouement was brilliant.) Good showings too for Michael Innes, and of course Gladys Mitchell.

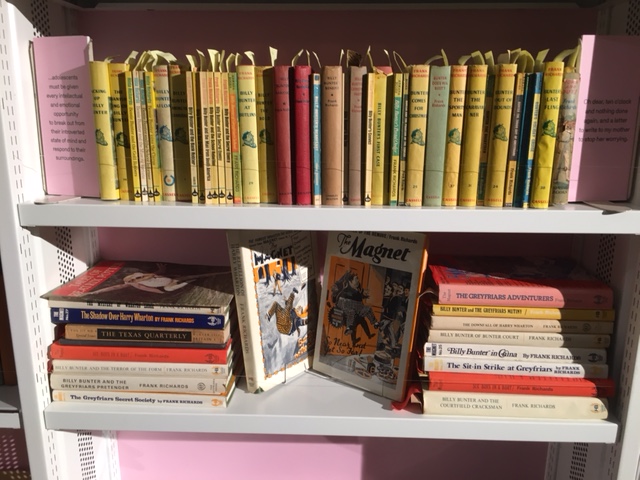

What I hadn’t expected to find was the double shelf of Greyfriars material pictured above. Larkin, of course, would have been of an age to read the Magnet weekly, in its later years before the advent of the Second World War shut it down. These books, though, show that his enthusiasm for Harry Wharton and Co. carried on well after that. Most of the books are paperback reprints from the sixties and seventies, and the bigger tomes are the Howard Baker collectors’ reprints from the seventies.

I knew, of course, that Larkin was fond of girls’ school fiction (I must re-read Trouble at Willow Gables to see if I can find a Frank Richards influence there.) And now that I think of it, I remember that there are some Greyfriars phrases (‘Yaroo!’ and so forth) in the letters to Kingsley Amis. But this is a collection that shows real dedication.

If ever I write another thesis it will be on the influence of Frank Richards on later twentieth century literature. The prime exhibit will be Evelyn Waugh (who is also well represented on Larkin’s bookshelves.) Waugh was a keen reader of the Magnet while at school (an illicit reader, but all the keener for being illicit); the bold caricaturist style of his satire shows the influence of Richards, I’d say – though he went further, and in Llanabba created a school even more gloriously bizarre than Greyfriars.

If you want to see the Larkin exhibition in Hull you’ll have to rush. It closes on October 1st.

Hull is doing Larkin proud at the moment. Here’s a snap of me chatting with his statue at the railway station.

4 Comments

There are some enthusiastic mentions of Lawrence’s novels in Larkin’s letters to Monica Jones, though he seems to have kept quiet about his admiration with Kingsley Amis. Lawrence was also one of Larkin’s father’s favourite writers, I think.

And according to Andrew Motion, Larkin always wore a D.H.Lawrence t-shirt while mowing the grass:

“I can still see him stomping up and down the lawn with that mower, wearing his D H Lawrence T-shirt – he always wore that for mowing the lawn. He absolutely hated the job, he had this enormous garden and found the whole business of mowing it a mighty bore.”

See: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1393852/Larkins-lawnmower-cuts-it-as-a-relic.html

Two fine photographs and a fascinating text – thank you!

I wrote this a dozen or so years ago on another website. I hope it’s OK to quote it here:

‘In 1939, Orwell wrote about *The Magnet* in *Boys’ Weeklies*: “As for class-friction, trade unionism, strikes, slumps, unemployment, Fascism and civil war — not a mention.”

Well, he arrived in Barcelona on or about December 26th 1936, so he probably didn’t get to read *The Magnet* of that date. I’m reading it now. I’ve just got to Chapters 14-17, and the story has taken a turn Icertainly didn’t expect.

For a variety of reasons, Billy Bunter and the Famous Five are spending the Christmas holiday cruising on a yacht belonging to the uncle of a fifth-former (not a regular member of the cast) called Valentine Compton. The uncle is a dodgy and unsympathetic character, and he’s been making the yacht linger in the Bay of Biscay.

Bob Cherry says they may get “a squint at Spain.” Bunter’s reaction is one of alarm. “I say you fellows, we don’t want to get too near Spain. The silly idiots are shooting one another all over the shop there.”

Then, realising they’re a safe distance from the shore, his courage returns. “Seems rather a pity not to see something of the Spanish civil war now we’re on the spot — still, you fellows would hardly care for it, I dare say…But it’s all right! You’re far enough off from the Reds, and the rebels, and the rest of them. They can’t hurt you here.”

But then Captain Compton makes contact with a Spanish lugger, and Bunter again gets panicky. “I-I say, you fellows, d d-do you think they’re Spanish Reds? Or-or Spanish rebels? I-I don’t know t’other from which, but they’re all a lot of murderous beasts!”

Bob Cherry pretends that one of the men in the lugger “looks like General Franco” and Bunter vanishes. ” ‘Ha ha, ha!’ yelled the juniors. The idea of General Franco, the leader of the Spanish military revolution, standing at the tiller of a dingy coasting craft, made them yell.”

While Captain Compton trades what are obviously guns with the men on the lugger, the schoolboys are ordered below. The steward suggests they listen to Seville radio. ” ‘Jolly good idea!’ said Bob Cherry. ‘Might get Madrid, too, and hear about the wonderful victories on both sides. Shove it on, Rawlings!’ ”

The narrator comments that Harry Wharton “was aware that a civil war was raging in Spain, and both sides eager for supplies of munitions to carry on their murderous folly”, but Wharton can’t guess for whom Captain Compton is doing the gun-running. However, later that day they’re pursued and fired on by a cruiser. “He could not be sure, but he fancied that the cruiser was a Government craft, and that the cases of munitions had been handed to rebels on the lugger.”

Despite the yacht’s carrying the British flag, it’s fired on several times again. And then on the next page come the small ads for stamps, height increase and the prevention of blushing to which Orwell also referred.

The politics of these chapters are intriguing. There’s the authorial comment on murderous folly on both sides; there’s the irony about radio propaganda claiming victory on both sides; there’s the fact Captain Compton is, within the larger story, almost entirely a villain and is seen as selling arms to Franco; and there’s the false assurance that “they dare not fire on the British ensign” in an episode where a Spanish Government vessel does just that.’

There’s a bit more if I can find it…

*The Magnet* for January 2 1937 continues the story of the cruise. As they sail away from Spain, “the juniors were looking in the direction of that fair but unhappy land, where the embers of civil war still smouldered.”

They pick up a castaway called Senor Don Guzman Diaz. Compton, the Fifth Former, tells the Famous Five about him. “He belongs to Madrid, and got away from the city when General Franco attacked it with the rebel army. He sailed from Cartagena in a coasting brig. The brig was bombed by a plane — whether Red or Rebel he doesn’t know. It went down, and he thinks he was the only survivor. He had been hanging on that spar for more than twenty-four hours when we picked him up. Just a little episode of the Spanish civil war.”

Harry Wharton asks, “Has he told you which side he was on in the scrap?”

Compton replies. “Neither side, according to his own account…Most people in Spain, of course, are on neither side, and would be glad to see both mobs of scrapping swashbucklers kicked out of the country. From what Mr. Diaz says, all he wanted was to keep clear, and he’s glad to find himself under the British ensign…In a foreign country he will be safe from both gangs.”

Johnny Bull says, “Well, those scrappers in Spain are a lawless lot of rotters on both sides. But bombing a coasting brig is rather thick!”

They go on to discuss the bombing and who might have done it.

Later on, the smugglers who are secretly running the cruise ship discuss robbing Senor Diaz of his well-stuffed wallet and putting him ashore on Majorca. “I suppose he knew what he was risking when he took a hand in a civil war!…I don’t know which side has the upper hand in the Spanish islands at the moment — he can take his chance of that! A man who doesn’t want to take chances has only to stick to honest work, and leave revolutions alone!”

The schoolboys are still “sympathetic enough towards a man who had been through so fearful an adventure, though in more than one mind there was a lingering doubt whether he had given an exactly veracious account of that adventure.

It was possible, of course, that his account was true, and that he was, as he had stated, a non-combatant who had been only anxious to get out of a country torn by internal strife. But as the vessel he had sailed in had been bombed at sea, it was much more probable that that vessel had belonged to one of the contending factions.”

The man tells them a bit more. “Don Guzman gave the Greyfriars fellows a description of the air bombing of Madrid by General Franco’s forces. Evidently he had been through it; though he made no reference to any part he might have played himself in the civil war. But when he spoke of the black African troops employed by the rebel general against his own countrymen, his eyes flashed and his teeth gleamed under his black moustache in a way which sufficiently showed on which side his sympathy lay…But that he belonged to the losing side, and was a fugitive from the victors, the juniors did not doubt.

They knew too little about Spanish affairs to have any decided opinion about the rights or wrongs of the civil war; in fact, they regarded it as a sort of case of Kilkenny cats! But they rather liked Don Guzman, who seemed a very courteous and agreeable old bean. Certainly they were glad that he had been rescued and was on his way to safety in a foreign country.”

This is, of course, very naive stuff. But it seems worth mentioning that it doesn’t take the line of ‘Thank God for Franco who is saving Christian civilisation from godless bolshevism.’

There also seems to be something gentler and more compassionate here than Orwell’s pungent final phrase ‘sodden in the worst illusions of 1910’ would perhaps suggest.

One Trackback/Pingback

[…] George Simmers has recently posted on his weblog Great War Fiction a report of his visit to an exhibit of volumes from Philip Larkin’s personal library. This was at the University of […]